Celebrate the turning season and a sense of renewal with the southwest’s wassailing tradition

With a mug of steaming spiced cider in hand, I look out as the light dances on the trees from dozens of flaming torches. Our breath cold as we start to sing – our voices joining in an uneven chorus, half song, half shout, the kind of sound that seems to sit somewhere between ritual and riot.

The annual tradition of wassailing marks the start of the year for many of us in the southwest. This Anglo-Saxon ritual brings communities together to bless the orchards for a fruitful harvest ahead. Deriving from the Old English wæs hæil – “be in good health” – the tradition has enjoyed a resurgence in recent years, with orchards and community gardens across the region seeing in the new year with cider, song and dance.

Historically, the Christmas period extended into early January, ending with feasting and revelry on Twelfth Night, when wassailing took centre stage. These days, wassailing celebrations stretch right into March. But what exactly makes a wassail – and why do these gatherings seem to resonate now more than ever?

Today, the ritual begins where it always has – among the trees. At this time of year, orchards are in limbo: pruning has been done, the ground lies wet and heavy, and the buds have yet to break. For growers, it’s a quiet moment before the year turns again – when you begin to think about what the next harvest might bring.

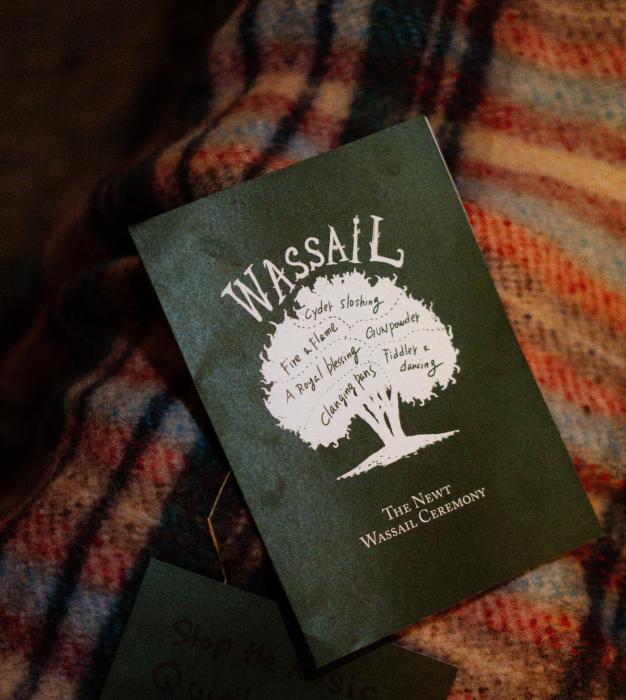

A master of ceremonies, known as the wassail king or queen, leads revellers down to the orchard to gather around the oldest tree. At the Newt in Somerset, this tradition has evolved, with a wassail prince and princess – usually staff members’ children – leading the proceedings. “We feel like these old traditions should be observed by the next generation,” explains Arthur Cole, head of programmes at the Newt.

Traditionally, pieces of toast are placed in the branches of the tree to entice robins, believed to be the guardians of the orchard. At Dyrham Park, master of ceremonies Tom Boden encourages visitors to dunk toast in apple juice and tuck it into the fruit trees as they pass along the procession. “We start in the Nicholls orchard – a perry pear orchard that dates back to the 17th century – and finish in the West Avenue, where we now have a collection of heritage apples.”

Cider is poured over the roots of the tree for good harvest, while everyone takes a sip from the communal wassail bowl. Dyrham Park even has a 17th-century example in its collection. The traditional tipple is usually a local ale or cider, blended with honey and spices, and made from roasted, crushed apples – a frothy drink known as Lambswool. At some wassails, you might be treated to a slice of Twelfth Night cake, a rich fruit cake baked with a hidden bean or pea to crown the king or queen for the night.

In a loud hullabaloo, pots and pans are clattered to ward off spirits and rouse the trees from their winter slumber. At the Newt in Somerset, the historical re-enactment group Marquess of Winchester’s Regiment has performed with drummers, artillery and even a Civil War cannon.

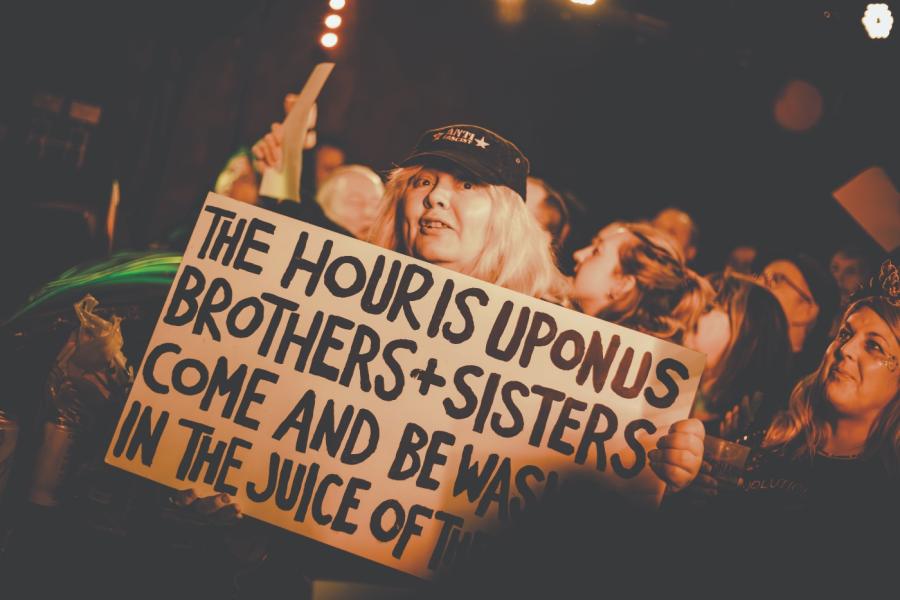

And then comes the music. We serenade the tree with wassail chants and traditional songs. Choruses of “Wassail, wassail, all over the town, our toast it is white and our ale it is brown!” spill out of Gloucestershire orchards in the late-winter hush. “Despite the frigid time of year, the atmosphere at a wassail is warm and inviting,” explains Sorrel Wilde, who leads the singing group at Hillfields Community Garden’s wassail. “The songs are made to get people moving – they have to be rousing to counter the cold.”

Wilde explains that there are two main types of wassail songs: orchard wassails, a more recent form that focuses on blessing the trees, and visiting wassails – an older form of door-to-door singing, closer to carolling or souling.

Some events keep things traditional, while others lean into the rowdier side. The Skimmity Hitchers, who describe themselves as purveyors of “scrumpy and western music”, perform at wassails across the southwest. “We’re cider to the core,” frontman Tatty Smart says. “Wassails are all about community, tradition, cider and mischief.”

The Bristol Urban Wassail, where they’ll headline in 2026, brings the tradition into the city. “It celebrates the hidden orchards and solo trees holding out in the shadows of the city, and the small producers making batches of scrump from their backyards,” Smart explains. “It’s a bit punkier than the traditional wassail, but it’s for the city dwellers who revere the holy apple as much as their rural counterparts.”

After the singing comes the dancing. The jangle of bells and clash of sticks mark the arrival of the morris sides – a newer, but now familiar, part of many wassails, alongside mummers’ plays. Among them is Wild Moon Morris, a Somerset group whose dark-border style – black and silver tatters, top hats, face paint – fits the midwinter mood. “A wassail needs to scare evil spirits from the orchards,” says the side’s squire, Mandy Knight. “We make sure to make enough ruckus to send them packing.”

She says the winter events give dancers a reason to get out again after their months of indoor practice. “By January, we’re champing at the bit. Wassails are the perfect light in the darker months.” Mostly held after dark, the performances take on a different atmosphere: “Some use candles, others fairy lights – compared to our dances in the summer sun, wassails feel peaceful.”

Like many border sides, Wild Moon sometimes cross into Wales for the Chepstow wassail, where revellers join the Mari Lwyd – a ribboned horse’s skull – to roam the streets, travelling from house to house and performing song battles for food and drink. “It’s closer to the Christmas traditions,” she says, “but the heart’s the same – it’s about music, song and blessing the trees for the new harvest.” For Mandy, the orchards remain at the heart of all wassailing traditions, both ancient and modern. “Wassails aren’t just a folk tradition, but a modern way of keeping orchards flourishing – whether it’s by scaring away evil spirits from the trees or by drawing in a crowd who will keep these businesses thriving.”

While the wassail tradition is a lot about noise-making, it’s also about quiet craftsmanship and people coming together to create a moment. At Dyrham Park, visitors are invited to a workshop beforehand, where they learn how to make their own wassail sticks to wave and clash together as part of the procession.

As the torches burn down and people make their way home, the orchard falls quiet. The frost settles on the trees, and the cider bowls have been drunk dry. The trees stand dark, toast still hanging from their branches. By morning, the robins will have played their part too. For all the noise and theatre, the true charm of the wassail is in its simplicity – a reason to gather together outdoors, mark the passing of the seasons, and to feel, if only briefly, connected to the land and one another.

Bristol Urban Wassail

16 Jan, 7 - 11pm

Exchange, Bristol

Hillfields Wassail

17 Jan, 2 - 4pm

Hillfields Community Garden, Bristol

Mid-Somerset Agricultural Society Wassail

14 Jan, 7 - 10pm

The Mid-Somerset Showground, Shepton Mallet

Midsomer Norton Wassail

31 Jan, 10am - 3pm

Midsomer North Market Square, Radstock

RCG Wassail

14 Jan, 1:30 - 4pm

Redcatch Community Garden, Bristol

Somerset Wassail @ Rich's

17 Jan, 7:30 - 11pm

Rich's Cider Farm, Highbridge

The Newt Wassail

6 Mar, 12 - 6pm

The Newt, Castle Cary

Wassail

17 Jan, 7 - 10pm

Somerset Rural Life Museum, Glastonbury

Wassail at The Community Farm

31 Jan, 1 - 3:30pm

Community Farm, Chew Magna, Bristol

Wassail at The Shoemakers

18 Jan, 2 - 4:30pm

The Shoemakers Museum, Street

Wassail Celebration

3 Jan, 12 - 2:30pm

Dyrham Park, Bath